Highlights From the Mass General Brigham 2025 Gene and Cell Therapy Institute Research Symposium

December 23, 2025

On December 11-12, 2025 Mass General Brigham held its 2025 Gene and Cell Therapy Institute Research Symposium. It included talks from scientists across the Boston / Cambridge ecosystem and keynotes from Dr. Carl June and Dr. David Liu. It was a privilege to be part of the mostly academic crowd. Despite leaning heavily academic, the speaker lineup was squarely focused on translation of the science and most, if not all, of the speakers have strong ties to commercial development and industry through startup companies based on their work, serving on boards, and consulting.

One of the highlights for me was the fireside chat featuring former FDA Director of the Center for Biologic Evaluation, Peter Marks. He and Mimi Lee gave interesting insights into the chaos of 2025 and how we should think about it moving forward.

Thinking across the talks some trends stood out:

Scale, speed, and systems are the primary barriers to bringing gene and cell therapies to market. Across CAR-T, base/prime editing, and regulatory perspectives, the speakers converged on the same conclusion: the core technologies work. The limiting factors are manufacturing, regulatory repetition, patient stratification, and the economics of developing thousands of bespoke therapies for rare genetic diseases. Basic science is no longer the bottleneck.

Platforms beat one-off drugs. If you can set aside the wax and wane of enthusiasm for platforms among investors. Platforms that amortize development risk will facilitate patient access to cell and gene therapies. Whether through armored CAR-T cells, mutation-agnostic gene integration, disease-agnostic editing strategies, or manufacturing platform and process thinking. The speakers (even the industry and former FDA folks) emphasized collapsing many patients, mutations, or indications into shared platforms.

Precision enables pragmatism. Advances in gene editor engineering, delivery, and computational design are not just high flying Nature, Science, and Cell publications. They unlock faster development timelines, safer profiles, and new regulatory pathways, making it realistic to move from heroic single-patient efforts toward scalable, sustainable clinical impact.

Manufacturing has emerged as both the quiet enabler and the dominant constraint. Across sessions, speakers highlighted real progress such as shorter vein-to-vein times for autologous CAR-T therapy, automation and closed systems, in vivo LNP delivery, and immune-evasive DNA donors. Along with the wins, persistent gaps were underscored: reproducibility at scale, cost, regulatory lock-step around CMC, and the lack of standardized “platform manufacturing” that can be reused across mutations or indications.

Below are some of the specific highlights from the talks given by Dr. Carl June, Dr. David Liu, and Dr. Ben Kleinstiver, as well as the regulatory fireside chat with Peter Marks and Mimi Lee.

Dr. Carl June’s Keynote Presentation

CAR-T has moved from “petri dish proof” to durable, living drugs. Dr. June traced the lineage from early receptor-fusion concepts (1980s) to Penn’s CD19 CAR-T experience starting in 2010. He highlighted real-world durability (e.g., long-term CAR persistence and B-cell aplasia) that helped de-risk early fears of “Frankenstein cells” that many known unknowns and even more unknown unknowns. The platform is now a global industry (7 FDA-approved autologous CAR-Ts in blood cancers; ~50,000 patients treated), with continued focus on lowering cost. It blew my mind when he talked about shrinking vein-to-vein time, from historically ~22+ days to currently running trials with ~3 days, and expecting to reach ~1 day soon.

Next-gen “armored” CAR-Ts are showing credible rescue potential in CAR-refractory disease. An investigator-initiated trial in CAR relapse lymphoma used CD19 CAR-T cells further engineered to secrete IL-18 (chosen for a favorable safety “brake” via IL-18 binding protein). In 21 heavily pretreated CAR-refractory patients, strong efficacy was reported, ~80% response, and unexpectedly high potency even at low starting dose was observed. These findings support the thesis that engineered cytokine payloads can rewire the microenvironment without unacceptable systemic toxicity.

Cytokine “receptor rewiring” may reverse exhaustion. Engineering CAR-T cells to express an IL-9 receptor (normally absent on T cells) produced an unexpected phenotype. CAR-T cells improved with repeated antigen stimulation, with STAT4 upregulation and reduced integrated stress response signaling. His data showed striking potency in mouse solid-tumor models.

Solid tumors remain a TME problem, not just a target problem. He framed solid tumors as an immunosuppressive, physically restrictive ecosystem (hypoxia, acidity, CAF/scar barriers), requiring CAR-T cell-intrinsic upgrades (cytokine arming, receptor rewiring, gene editing) plus cell-extrinsic combinations (co-therapies that remodel the TME).

Multiplex base editing + in vivo CAR engineering are the commercialization inflection points. Dr. June underscored the problem with trying multiplex editing with Cas9, that is many double strand breaks lead to translocations and cell death. Base editing may overcome that problem. He showed base editing with an ABE enabled ~20 simultaneous edits at high efficiency, opening design space for allogeneic/off-the-shelf products (target choice becomes the limiter, not edit count).

A wave of in vivo CAR therapies and autoimmune diseases indications are coming. CAR-T is expanding beyond cancer to autoimmune diseases, where positive data has been in systemic lupus erythematosus, idiopathic myopathy, scleroderma, and fibrosis. A landmark German study used existing CAR-T therapy to achieve a 100% response rate by resetting the immune system. The future of this field lies in in vivo therapy: using lipid nanoparticles to reprogram T cells directly inside the patient’s body via a simple injection. This "off-the-shelf" mRNA approach could eliminate complex lab manufacturing and is well-positioned to treat autoimmune disease. The trend is demonstrated by a growing number of clinical stage companies developing in vivo CAR-T therapies for autoimmune indications.

“Fireside Chat: Regulatory Landscape in CGT and Rare Diseases”, Panelists: Peter Marks, MD, PhD and Mimi Lee, MD, PhD, Moderator: Angela Shen, MD, MBA

The “2025 chaos” at FDA is mostly noise for early programs, but late-stage sponsors should diversify geographies. If you’re preclinical/Phase 1–2, the political/regulatory turbulence is likely to clear before you file; for Phase 3+ assets, don’t assume the U.S. is the only path. Other regulators (UK, Australia, China, etc.) are “open for business.” Treat the instability as a forcing function to test creative, pro-innovation regulatory concepts, even if credit-taking gets messy.

Rare/ultra-rare genetic medicines need a platform + process regulatory paradigm, not “one BLA per construct.” The current model over-penalizes Type I error (false positives) at the expense of Type II error (false negatives) in tiny populations. For indications with small patient populations, insisting on bespoke animal models and repeated tox packages becomes economically absurd. A more rational approach would be to approve bounded platforms (e.g., a defined editor + delivery system + manufacturing controls) so developers can move between constructs without restarting from zero.

Manufacturing is the real rate-limiter and the #1 driver of complete response letters (i.e. rejections) from the FDA. Reproducibility and characterization at scale is the most common failure mode at BLA time, especially for AAV. (Side note on AAV: I saw Dr. Marks talk at an mRNA therapeutics conference where he previously suggested AAV would be a “historic blip” due to difficulties with manufacturing and a few other problems). Both panelists converged on automation (“robots can do this”) and standardized micro-factories as prerequisites to faster development and lower prices. Both of which are essential to bringing down the cost for patients and making it make sense for payors to cover. This is becoming more accessible as modalities shift toward LNP/mRNA/editors that behave more like chemistry than biology. When it comes to manufacturing, plan earlier and automate aggressively.

Sequencing as national infrastructure is strategically obvious and politically hard. Universal sequencing is an accelerant for diagnosis, cohort-finding, and bespoke therapy design. It’s a delicate balancing act to execute and implement universal sequencing while maintaining patient-controlled data architectures and privacy. The U.S. is behind some other countries in realizing population level sequencing, the friction points being distrust of centralized data, state-by-state variation even in newborn screening, among others. An opt-out and education will be essential.

Some of the noise coming from the FDA is merely opinion and will be challenged in court. Much of what the FDA has been saying publicly through issued guidance and editorials are merely opinion pieces and either aren’t substantive or will be challenged in court. For example, implying superiority trials as a default bar for drug approval. Other events, such as the Pediatric Priority Review Voucher (PRV) expiration, will have near-term funding consequences for rare disease developers. It was suggested to get a good attorney to help differentiate signal from noise and understand the probability of real consequences of the rhetoric and proposed changes.

Dr. David Liu's Keynote Presentation

Three editing paradigms map to three commercialization strategies. Dr. Liu framed therapeutic genome editing as (i) mutation-specific correction (base and prime editing), (ii) mutation-agnostic repair (targeted gene integration), and (iii) disease-agnostic rescue (pathway-level fixes that unify patients across genes). Scientific design choices can directly address non-scientific bottlenecks such as regulatory repetition, manufacturing cost, and cohort fragmentation.

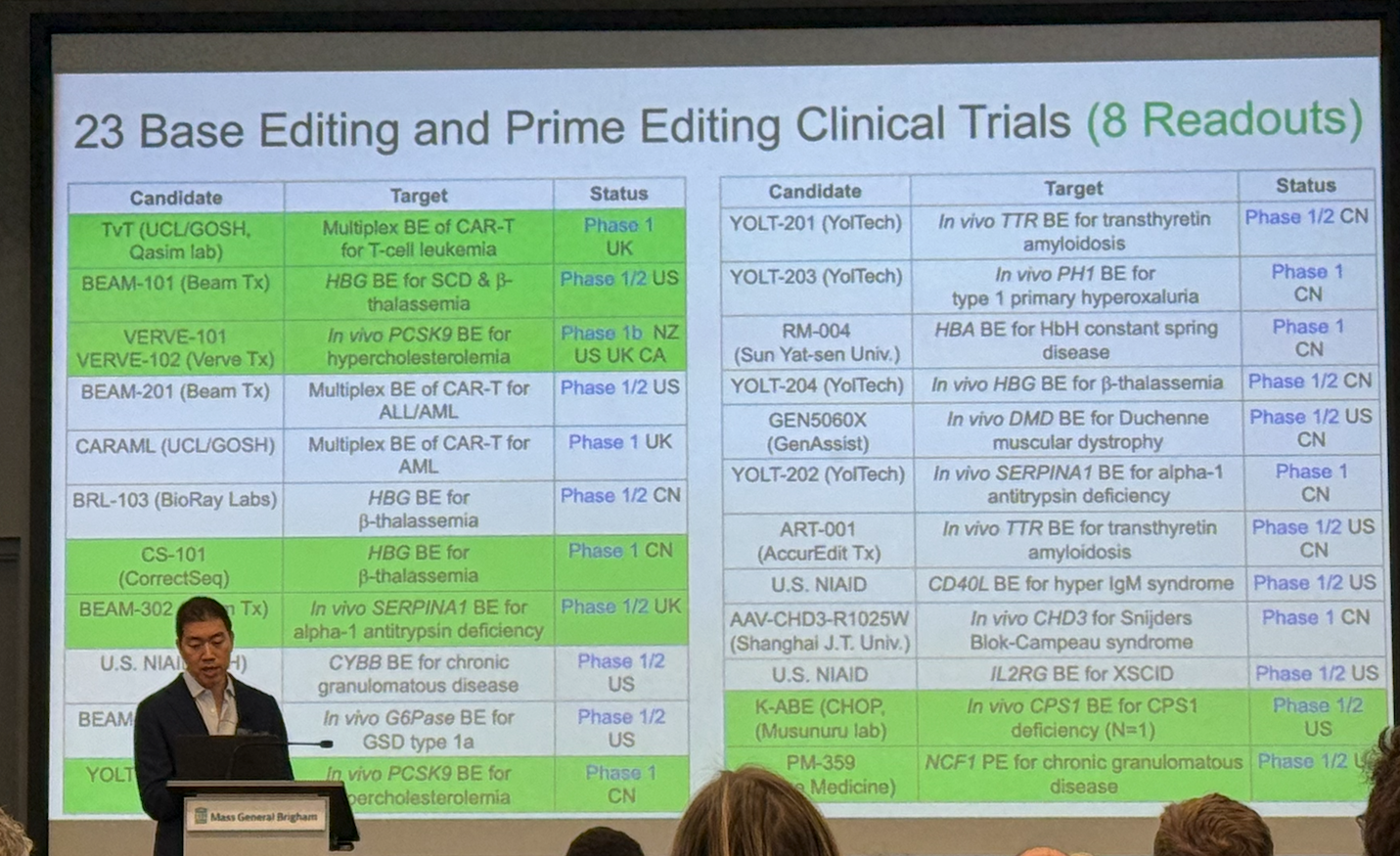

Mutation-specific editing is already delivering clinical firsts. Base and prime editors, engineered to avoid double-strand breaks, are now in 20+ clinical trials (mostly in vivo), with eight reporting patient benefit. 2025 milestones included:

Durable remission after base-edited CAR-T for T-cell leukemia

Autologous HSC base editing for sickle cell disease eliminating pain crises

In vivo base editing of PCSK9 lowering LDL by ~60%

The first direct correction of a pathogenic mutation in a human in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency disease

A bespoke, single-patient editor developed in ~7 months for infant CPS1 deficiency.

Prime editing also showed early human efficacy in chronic granulomatous disease, highlighting its precision advantage when bystander edits limit base editing

Mutation-agnostic repair aims to collapse thousands of alleles into one drug platform. Liu highlighted two routes to targeted gene addition that preserve native regulation: (a) prime editing + recombinase landing sites (PASSIGE) and (b) evolved CRISPR-associated transposases (EvoCAST). Using continuous protein evolution, EvoCAST boosted mammalian integration >200–350× over nature, achieving ~10–30% targeted insertion at disease loci without indels, a practical threshold for many loss-of-function disorders.

Disease-agnostic editing could unify patients across genes and diseases. A third strategy, PERT (prime-editing endogenous tRNAs into optimized suppressors), rescues premature stop codons (~25–30% of pathogenic alleles) with a single composition of matter. In human cell models across Batten, Tay-Sachs, and Niemann-Pick, one editor restored 20–70% function with minimal global translation effects. In vivo it rescued Hurler syndrome pathology, suggesting a scalable way to treat many rare diseases without one-drug-per-mutation economics.

Dr. Ben Kleinstiver's Presentation

Tackling Cas9 “PAM constraints” as a major gating factor for therapeutic base editing. Wild-type Cas9 can only bind and edit where a compatible PAM exists, which blocks many clinically relevant mutations. Dr. Kleinstiver’s group first built PAM-relaxed and near-PAMless enzymes to access almost any base. The trade-off of PAMless Cas9 is that broader genome access can increase off-target encounter risk because PAMs also act as a targeting mechanism.

Replacing one PAMless editor with a toolbox of bespoke editors designed ad hoc. One of Dr. Kleinstiver’s grad students, Rachel Silverstein, characterized ~1,000 engineered Cas9 variants and used them to train a machine-learning model that maps Cas9 sequence to PAM/DNA sequence targeting preferences. The practical output is a workflow (and web tool) where you input a target sequence for editing (and optional “avoid” off-targets) and receive custom Cas9 protein sequences predicted to maximize on-target activity while minimizing undesired binding, enabling allele-level discrimination (even single-nucleotide differences).

Clinical translation case study: Baby KJ (CPS1 urea cycle disorder) showcased “design-to-drug” speed. The CPS1 mutation was base-editable but not addressable with wild-type Cas9 due to missing PAMs. A PAMless editor worked, but safety/precision concerns pushed the team to an ML-designed Cas9 that delivered high (near-saturating) editing that was also more selective, lowering the risk of off-target edits. The treatment ultimately reduced ammonia and allowed discharge home on a near-normal diet.

Large DNA insertion is bottlenecked by innate immunity but can be overcome with nucleic acid engineering. Many recombinases/transposases require large dsDNA donors, but cGAS–STING senses cytosolic dsDNA, triggering toxicity and possibly lethality. To get around this Dr. Kleinstiver’s lab developed immune-evasive “chimeric” donors that had a circular ssDNA with only a short dsDNA patch where the recombinase enzyme binds. The recombinase is packaged in LNPs with the chimeric ssDNA/dsDNA donor and administered in vivo. Result: mice tolerated multi-mg/kg dosing with minimal STING activation and achieved ~1% bulk liver integration, potentially positioning non-viral in vivo insertion as plausible for select LOF diseases.

About the author

Steve Ouellette, PhD is the founder of Solidus Bio, a boutique consultancy focused on helping early stage companies and investors capture opportunity in the biotechnology space. He works closely with clients on projects related to due diligence, product development, IP strategy, and go-to-market strategy for research tools, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Feel free to reach out.