IP Review: Tessera’s Therapy for Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency Disease - Engineering a $150M Gene Editor

December 10, 2025

TL;DR

Tessera and Regeneron’s TSRA-196 enters the competitive field of in vivo gene editors for treating alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD).

A key enabling invention is a systematically engineered targeting RNA that achieves rewriting efficiency in excess of 70% with <1% introduction of errors in vivo.

Combined with Tessera’s IP portfolio around St1Cas9 compositions and LNPs, TSRA-196 looks like a strong lead asset for clinical and commercial impact.

Tessera Therapeutics and Regeneron announced a collaboration last week to co-develop TSRA-196, Tessera’s therapy for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency disease (AATD). The partnership includes a $150M up front payment to Tessera with an additional milestone payment of $125M, and potential to split future profits 50:50.

What goes into building a gene editor that commands a hefty price tag due to its in vivo data showing impressive levels of correction in the SERPINA1 gene? How does it work and what makes it unique?

A PCT application (PCT/US2025/020065) filed by Tessera published on September 18, 2025 titled “MODIFIED ST1CAS9 GUIDE NUCLEIC ACIDS” might give some insight.

The patent moat around TSRA-196 will likely include protection around the gene editing payload, LNP-based drug delivery compositions, specific formulations, methods of use, and other bells and whistles; this application addresses some of these but focuses specifically on the gene editing payload.

The innovation in the application is focused around components of a gene editing system based on a Cas9-reverse transcriptase (Cas9-RT) fusion protein and a template RNA (see prime editing). The template RNA directs the Cas9-RT fusion to the SERPINA1 gene and encodes the sequence to be written into the genome by the Cas9-RT that corrects the E342K mutation, which characterizes the PiZZ genotype of AATD, the most common form of the disease.

The engineering effort put forth by the Tessera team to build the template RNA goes far beyond the status quo guidelines for template RNA design and related design tools used in the field.

Let’s dive in.

The core innovation: an engineered tgRNA template

While optimizations of the whole system are described in the application, the star of the show is the heavily engineered and optimized RNA template that provides a targeting function to the gene editor and encodes the sequence to correct the SERPINA1 gene.

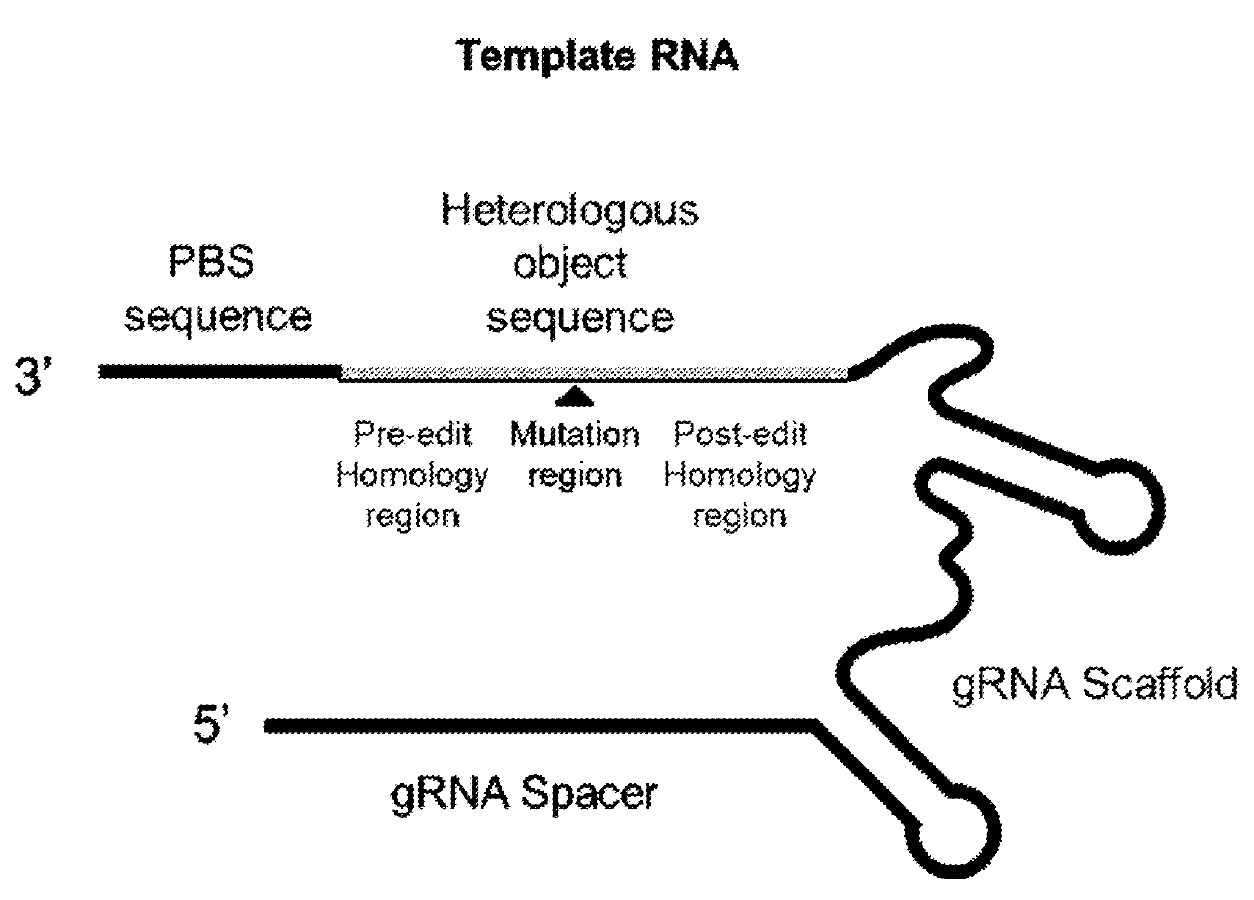

The RNA template, or tgRNA, has a set of sub-sequences that each provide a function to the gene editing system. The sub-sequences appear in the tgRNA sequence from 5’ to 3’ as follows:

gRNA spacer - has homology to and binds a target sequence in the genome to be edited

gRNA scaffold - interfaces with the Cas9 domain of the Cas9-RT fusion protein

heterologous object sequence - contains the sequence that will be written into the genome

primer binding site (PBS) - binds to a sequence adjacent to the target site to be altered

Overall structure of the template RNA, or tgRNA, that directs a Cas9-RT Fusion to SERPINA1. Image adapted from PCT/US2025/020065.

Taken together, the tgRNA is a multifunctional sequence that facilitates genomic editing by the Cas9-RT fusion. It localizes the fusion to the SERPINA1 gene adjacent to the E342K mutation and encodes the informational instructions for correcting it.

In practice, getting this to work efficiently is anything but straightforward. While there are some basic guidelines for designing the RNA template and its sub-sequences, there is no guarantee of success. A recent review of prime editing in mammals discusses optimization of the RNA template and even with the most recent design tools states “none offer a guarantee of editing efficiency, and the difference between expected editing efficiency and measured editing efficiency can be variable.”

So how did Tessera go about engineering the RNA template for correcting the E342K mutation in SERPINA1?

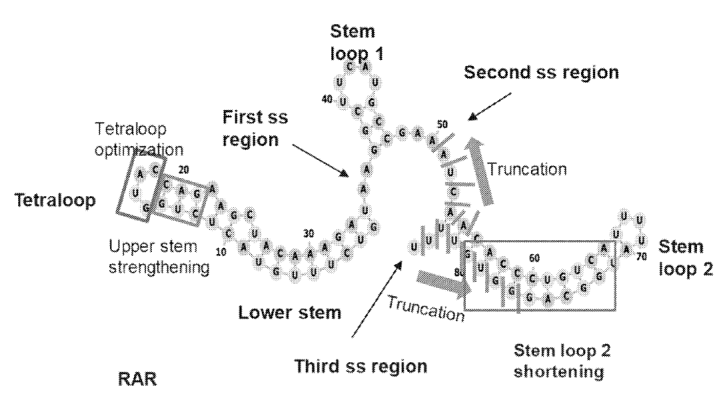

The team systematically engineered sub-sequences of the RNA template sequence to increase its stability and potential editing efficiency, which included:

Truncating the stem loop 2 motif at the 3’ end of the scaffold sequence to mitigate negative catalytic effects and improve target engagement by the PBS.

Strengthening the tetraloop upper stem by stem elongation and substitution with more stable loop bases to overcome RNA misfolding and facilitate Cas9 loading.

Tuning spacer length to optimize R-loop stability.

Varying PBS and the heterologous object sequence lengths to identify optimal priming and writing windows.

Overview of engineered regions of the scaffold sequence within the tgRNA. Image adapted from PCT/US2025/020065.

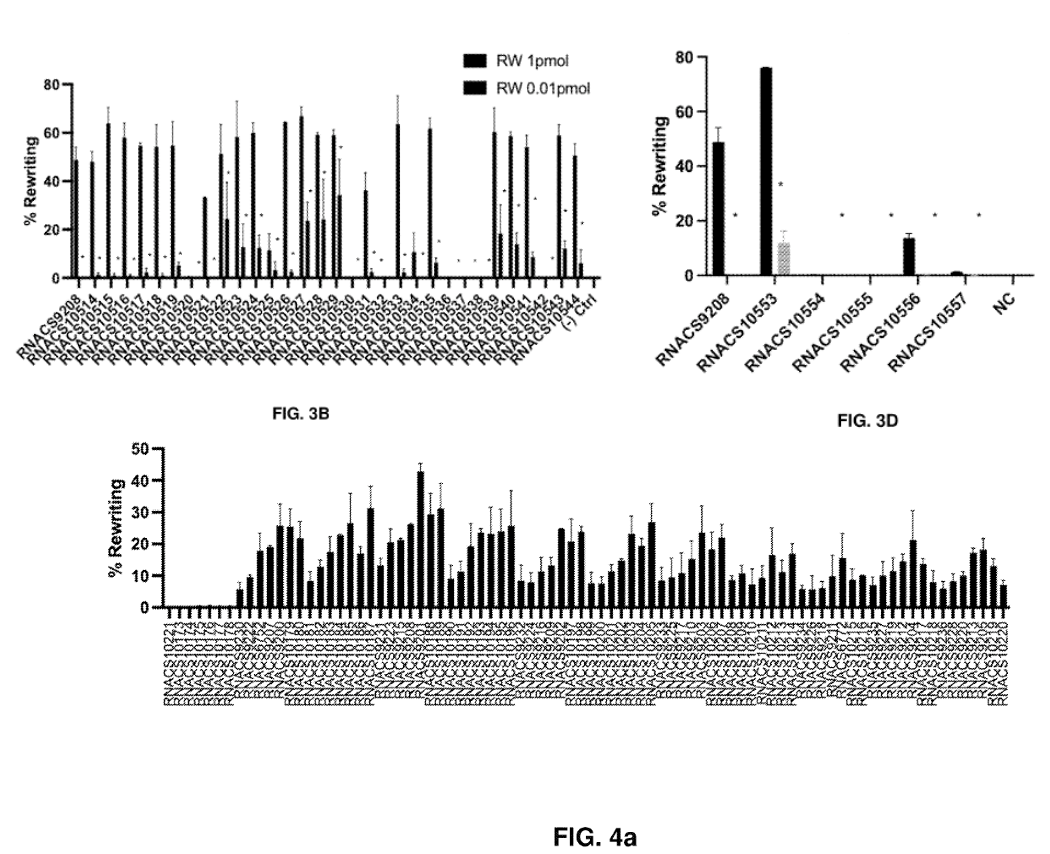

The Tessera team designed at least 7 spacer sequences, 150 gRNA scaffold sequences, 47 heterologous object sequences, and 12 primer binding site sequences (not counting the various patterns of chemical modifications to improve tgRNA stability).

This produces thousands of possible combinations. It’s not practical to synthesize and test every possible sequence, so instead the team evaluated each design variable systematically by measuring its impact on rewriting efficiency.

The team evaluated rewriting efficiency in a HEK293T cell model carrying the E342K mutation across panels of tgRNA templates with scaffold variants (FIG. 3B), spacer length variants (FIG. 3D), and priming and heterologous object sequence lengths (FIG. 4A).

Example results from the engineered tgRNA screening showing rewriting performance. Image adapted from PCT/US2025/020065.

They found that within the scaffold sequence, truncation of the stem loop 2 region, certain tetraloop variants in the repeat anti-repeat (RAR) region, and elongation of the stem structure and a longer spacer length facilitated improved rewriting efficiencies. Primer binding site sequence lengths between 6-10 nt and a heterologous sequence length less than 14 nt also appeared advantageous for rewriting.

Overall, the highest performing tgRNA showed >75% rewriting efficiency with less than 5% indels (i.e. rewriting errors) in the HEK293T model, and a set of other tgRNAs with rewriting efficiency >60% and <5% indels.

The team also demonstrated that rewriting efficiency can be further improved by the use of a second strand-target gRNA that targets the nickase activity to a second site. It is thought that a second nick can bias the DNA repair toward incorporation of the heterologous object sequence. However, it comes with the risk of introducing undesirable double strand breaks. Delivering a second gRNA also increases the complexity of the therapy, its formulation, and its manufacturing.

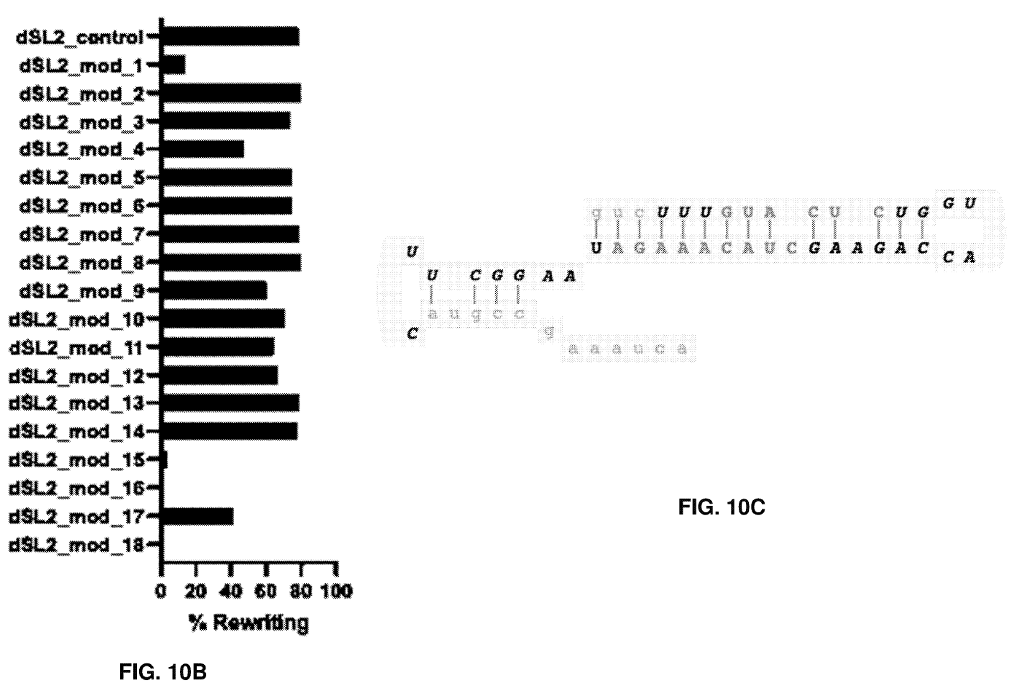

They then layered in patterns of chemical modifications to the tgRNA templates and identified positions in the tgRNA that are amenable to modification without sacrificing rewriting efficiency. For example, to identify the specific positions in the scaffold sequence, three nucleotides were modified at a time. The results showed that modifications in positions 1-3 and positions 43-54 decreased % rewriting, modifications in positions 7-12 and 25-33 are somewhat tolerated, and modifications in positions 13-24 and 34-42 are well tolerated (FIG. 10B-C).

FIG. 10B shows how different patterns of chemical modifications impact rewriting performance. FIG. 10C Shows Well-Tolerated (upper case) and Poorly Tolerated (lower case) Positions in the Scaffold Sequence. Adapted from PCT/US2025/020065.

After incorporating 2’-o-methyl groups and phosphorothioate linkages at positions determined to be well tolerated, the highest rewriting efficiency reported in the cell model was 71.89%. The tgRNA was further modified with 2’-fluororibose at the primer binding site sequence, as 2’-fluororibose can increase binding affinity of the PBS for the target genomic sequence.

Validation and Evaluation of the Optimized RNA templates in vivo

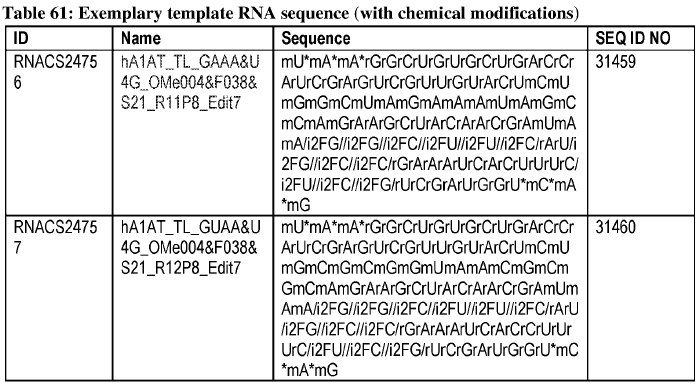

"Optimized" tgRNA with the chemical modifications were identified and had the following sequences:

Optimized tgRNA sequences with modifications. *=phosphorothioate linkage; m=2'-o-methyl; i2F=2’-fluororibose Image adapted from PCT/US2025/020065.

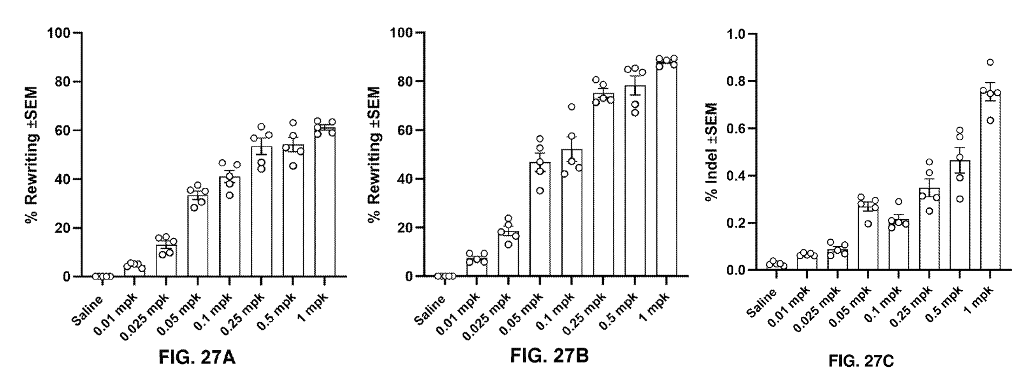

The templates were formulated in LNPs with "optimized" Cas9-RT fusion mRNA (more on that below), and administered to hSERPINA1 E342K transgenic mice intravenously in a dose-dependent manner (0.1 - 1 mg per kg). The % rewriting (FIG. 27A), % of corrected mRNA (FIG. 27B), and % indels (FIG. 27C) in liver tissue were evaluated.

Results from in vivo experiments showing dose-dependent effect of the gene editing on the SERPINA1 gene and resultant mRNA transcripts. Adapted from PCT/US2025/020065.

The results were beautiful - Dose-dependent increases in % rewriting in the hSERPINA1 gene translated to increased % rewriting at the mRNA level, while the % indels in the hSERPINA1 remained below ~0.8%.

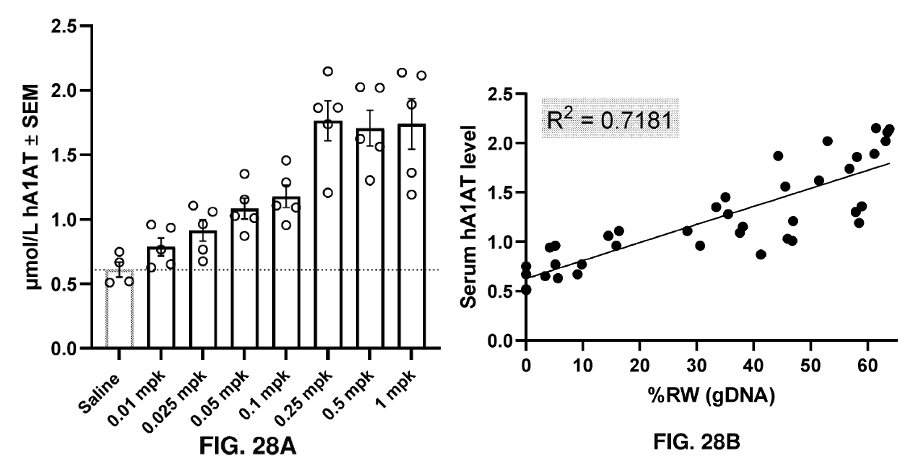

In patients, the E342K mutation in the SERPINA1 gene results in alpha-1 antitrypsin (A1AT) protein aggregation and decreased circulating A1AT. Circulating A1AT was measured in serum collected from the mice (FIG 28A). FIG. 28B shows a correlation analysis between circulating A1AT levels and rewriting activity.

Results from in vivo experiments showing dose-dependent increase in circulating A1AT and correlation with % writing at each dose level. Adapted from PCT/US2025/020065.

What about the Cas9-RT fusion protein?

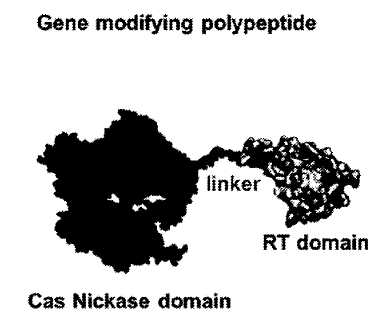

The Cas9-RT fusion protein in this gene editing system is described as a "gene modifying polypeptide" having a Cas9 nickase domain, a linker, and an RT domain.

Adapted from PCT/US2025/020065.

The application specifies that the tgRNA can be used with any one of ~7800 different sequences encoding the whole fusion or individual parts of it. Neither in the claims filed with the PCT application nor in the enumerated embodiments is there a claim on any of these sequences. The fusion protein itself is not the invention in this application.

So which Cas9-RT fusion are they using? There are a couple of hints.

In claim 21 of the PCT application a specific St1Cas9 sequence is cited as the Cas9 nickase domain. This tracks with the examples that describe an “optimized” Cas9-RT used to generate the highest impact data (FIGs 27-28 above). That optimized Cas9-RT has the same St1Cas9 sequence as in claim 21 along with an RT domain harboring a set of mutations described in the applications (if you’re interested in more details on this sequence please reach out). More telling is that another PCT application from Tessera published this year covers Sp1Cas9 compositions, including the “optimized” Cas9-RT sequence in this application.

That leaves the RT domain. A quick sequence search of the RT domain turned up only 2 other patent families, both owned by Flagship Pioneering. Given that Tessera is a Flagship company, there’s probably no major freedom to operate barriers there.

What about the LNP?

None of this works without a good delivery vehicle. Tessera owns IP protecting novel LNP compositions. What can we learn about the specific formulations for AATD gene editing systems?

In the application reviewed here, one example showed how lipid nanoparticle compositions were optimized for the delivery of the SERPINA1 modifying fusion and tgRNA. It points to example 44 in this patent family. There are other recent patent applications assigned to Tessera covering LNP compositions for delivering payloads for AATD therapeutics, here and here.

However, this one published earlier this year has an example of delivering LNP formulated SERPINA1 modifying payloads to mice. And the payloads look a lot like the tgRNA and fusions reviewed in this article.

Suffice to say, Tessera has plenty of LNP IP it can draw from for formulating its gene editing payloads.

Conclusion

TSRA-196 isn’t valuable because it’s a gene editor, it’s valuable because it’s an engineered system with dozens of interlocking optimizations that are hard to copy, hard to design around, and hard to match in vivo. That’s why this deal commanded $150M up front.

Importantly, Tessera appears to have strong IP on the tgRNA reviewed here, as well as the Cas9-RT fusion protein and the LNP components; all aspects of the in vivo editing system that make up TSRA-196. While a full IP diligence for TSRA-196 would require knowledge of the exact components that made it into the final formulation and a much deeper dive into this and other patent families owned by Tessera and its competitors, this review highlights the huge engineering effort that goes into complex in vivo gene editors. The engineered tgRNA is crucial to building an editor capable of correcting the SERPINA1 E342K mutation and potentially curing AATD. Combined with optimized Cas9-RT fusion proteins and LNP delivery systems, Tessera has a strong lead candidate in the making for advancing into the clinic, especially in view of the most recent data released publicly.

The first-in-human clinical trial was recently registered and will be a dose escalation, dose expansion, and single repeat dose study focused on identifying treatment-emergent and serious adverse events, pharmacokinetic profile of TSRA-196, effect of TSRA-196 on serum A1AT protein levels following treatment, and the effect of repeat dosing on serum A1AT protein levels.

Will TSRA-196 win the AATD market? It has some serious competition, with Beam Therapeutics and CRISPR Therapeutics also developing in vivo editors for AATD.

This will be an exciting race to watch!

About the author

Steve Ouellette, PhD is the founder of Solidus Bio, a boutique consultancy focused on helping early stage companies and investors capture opportunity in the biotechnology space. He works closely with clients on projects related to due diligence, product development, IP strategy, and go-to-market strategy for research tools, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Feel free to reach out.